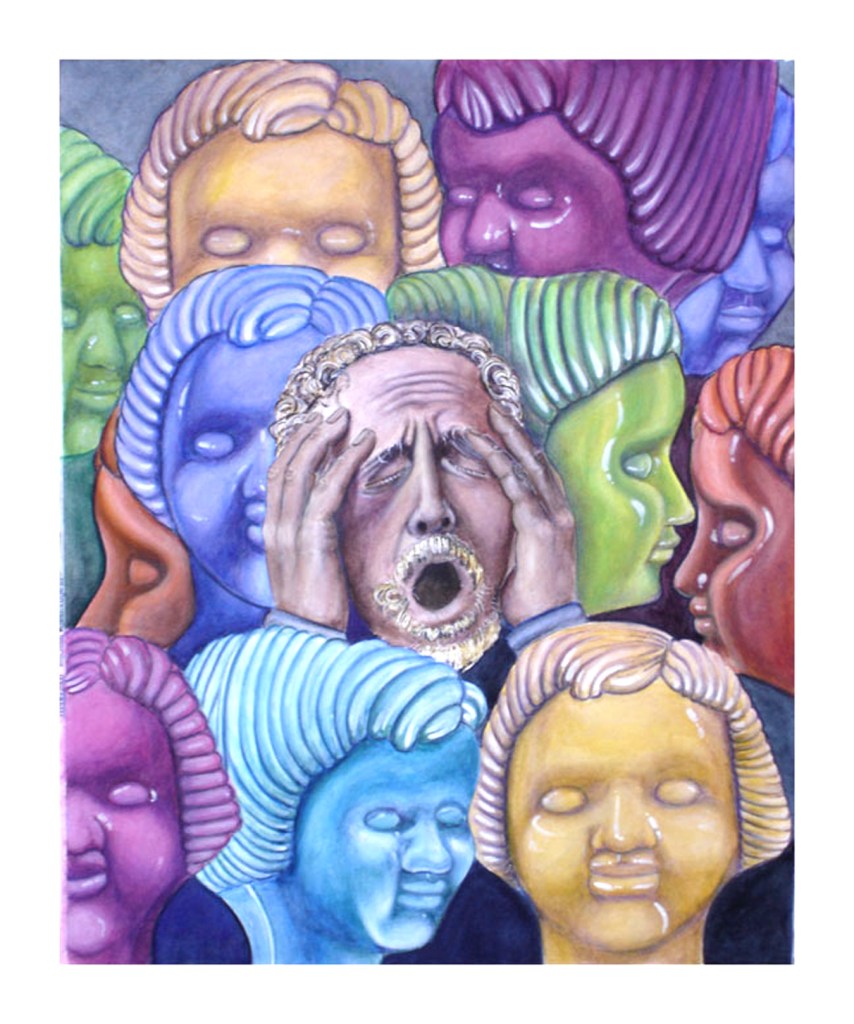

Having recently experienced deaths of a number of people close to me, I can’t help thinking about mortality and what may come next. Humankind has, of course conceived existence of some sort after death for as long as self-consciousness has been realized, and although the physical presence of those deceased will no longer be with us, they do live on in our memories even as we realize an emptiness in their absence.

Whether wishful thinking or a transcendental awareness, after life existence will never disappear as a concept, as widespread religious practice, dependent on such belief, affirms. Even the non-religious must harbor the notion of some sort of post-biological consciousness.

In any case, a healthy perspective will depend on reveling in the wonder of a fleeting daily existence.